A while back, one of our retail locations received a 2011 Dodge Ram 2500 equipped with the 545RFE transmission and the 5.7L engine with a neutral condition in higher gears. The customer stated that the transmission has had shifting issues for some time but did not elaborate on those issues.

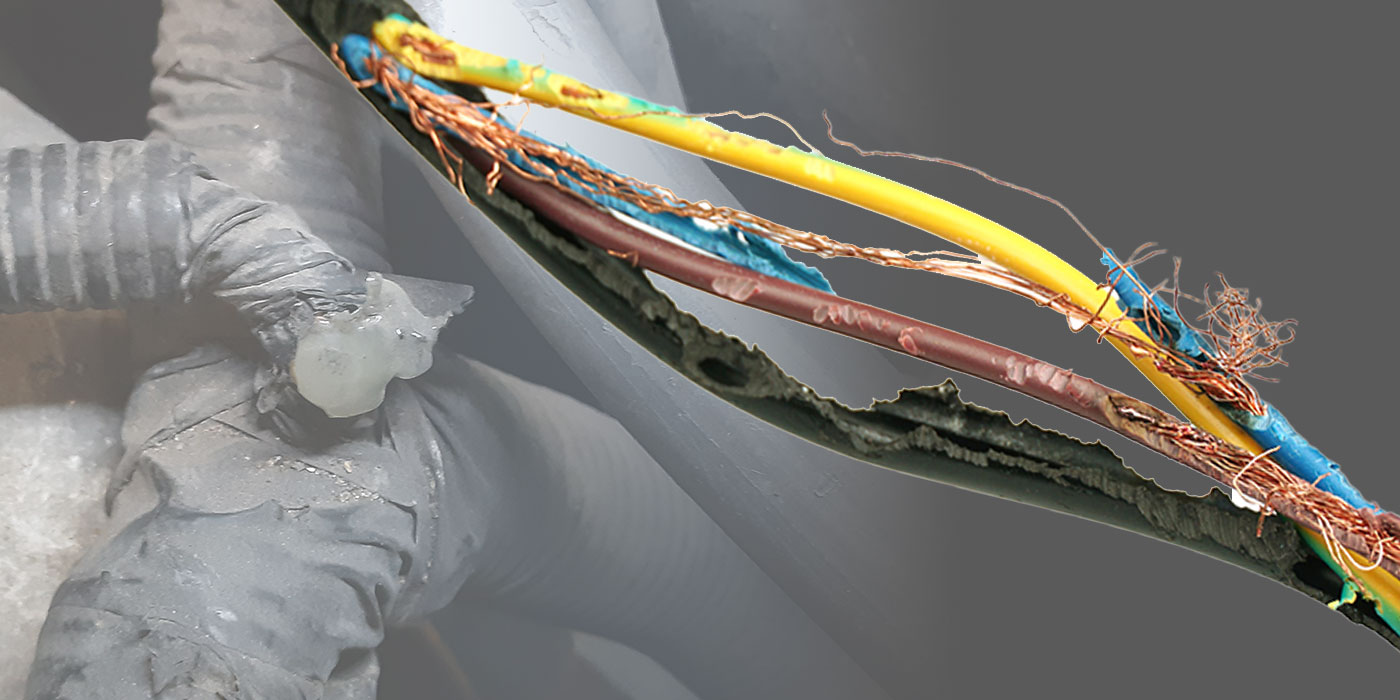

As I began the verification and diagnostic process, the first thing I noticed was severely corroded battery terminals, which would need to be addressed. Fluid was full and burnt. Scanning the truck for codes revealed P0734 and P0735. Both were gear ratio error codes for fourth and fifth gears, respectively. A road test did exhibit a neutral condition on the 3-4 shift command, but not surprising given the DTCs that were stored along with the customer complaint.

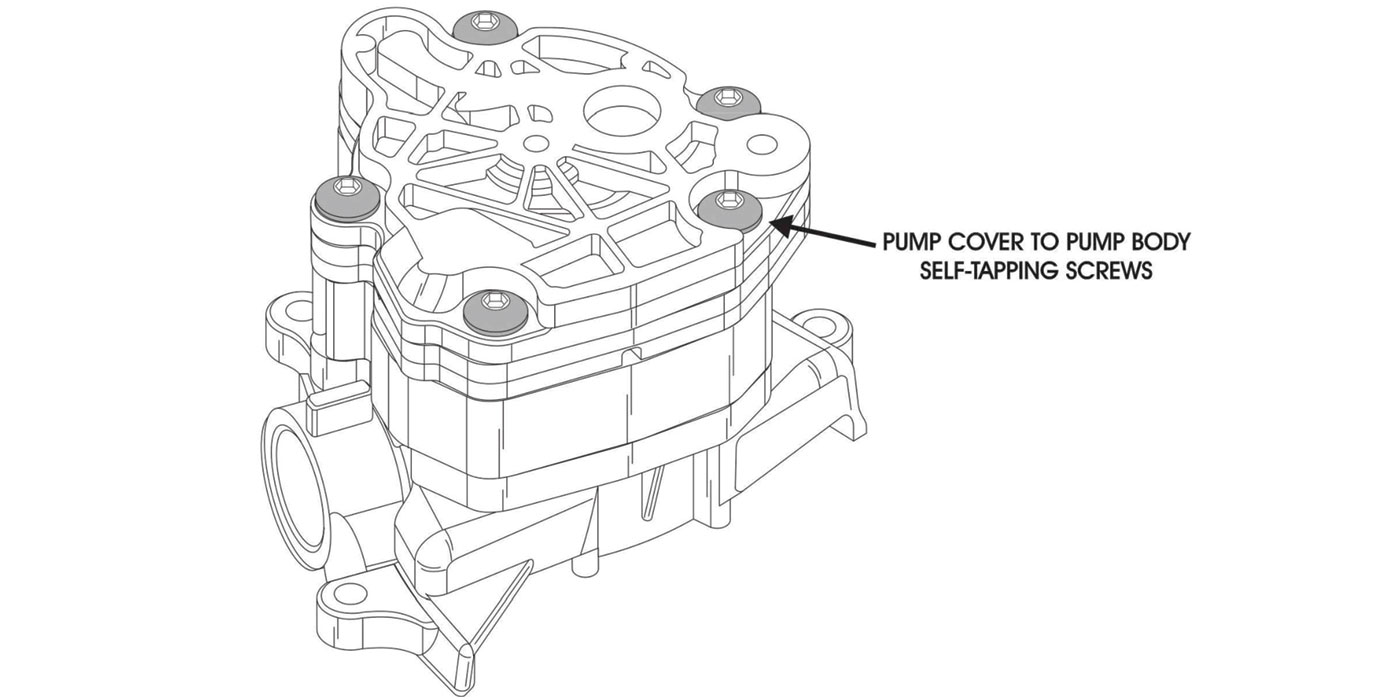

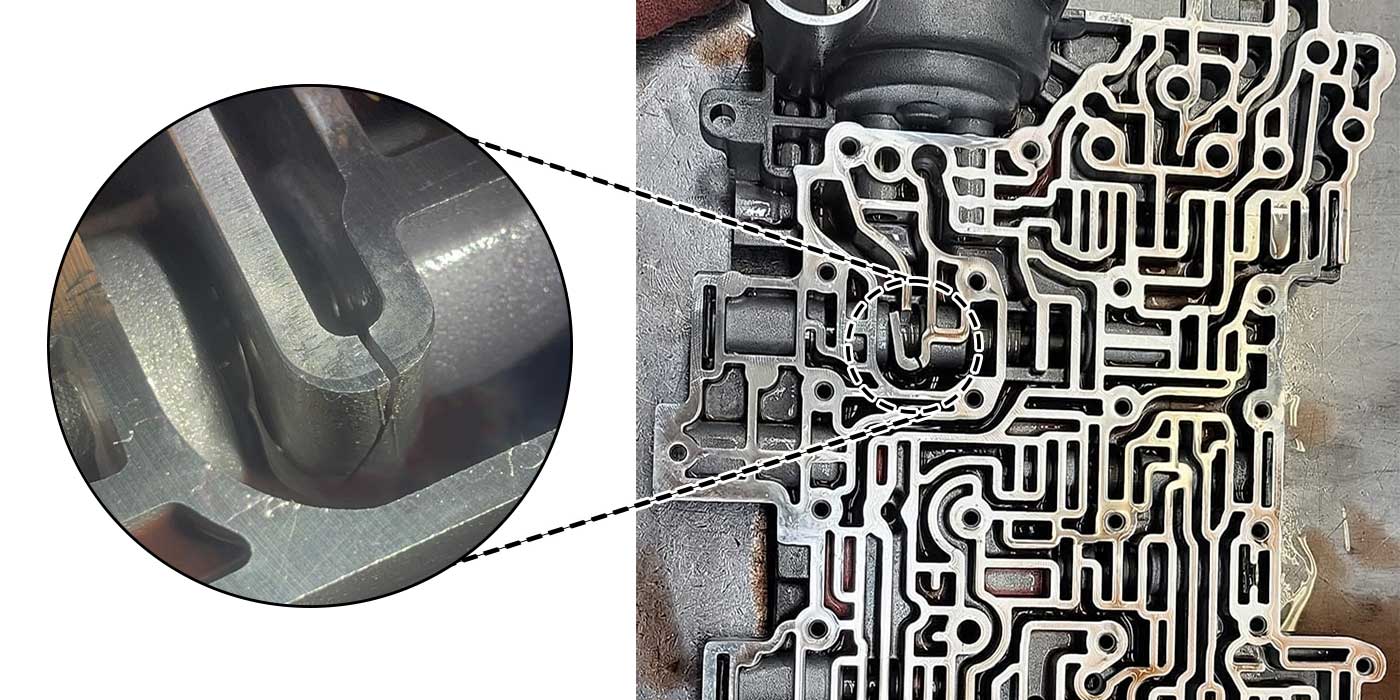

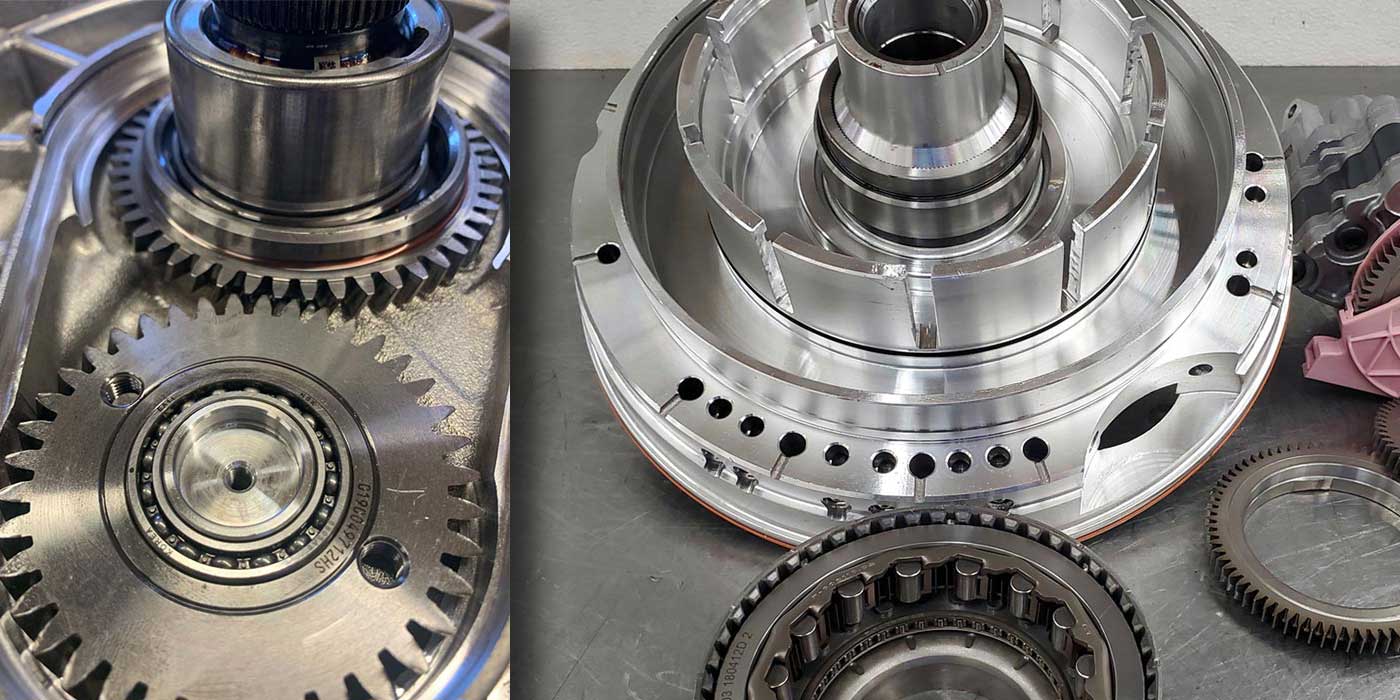

I suspected the accumulator plate was the culprit, so I performed a pan inspection and verified that it was indeed the cause of the failure. The pan and filter were also full of debris. This unit was done, or so I thought.

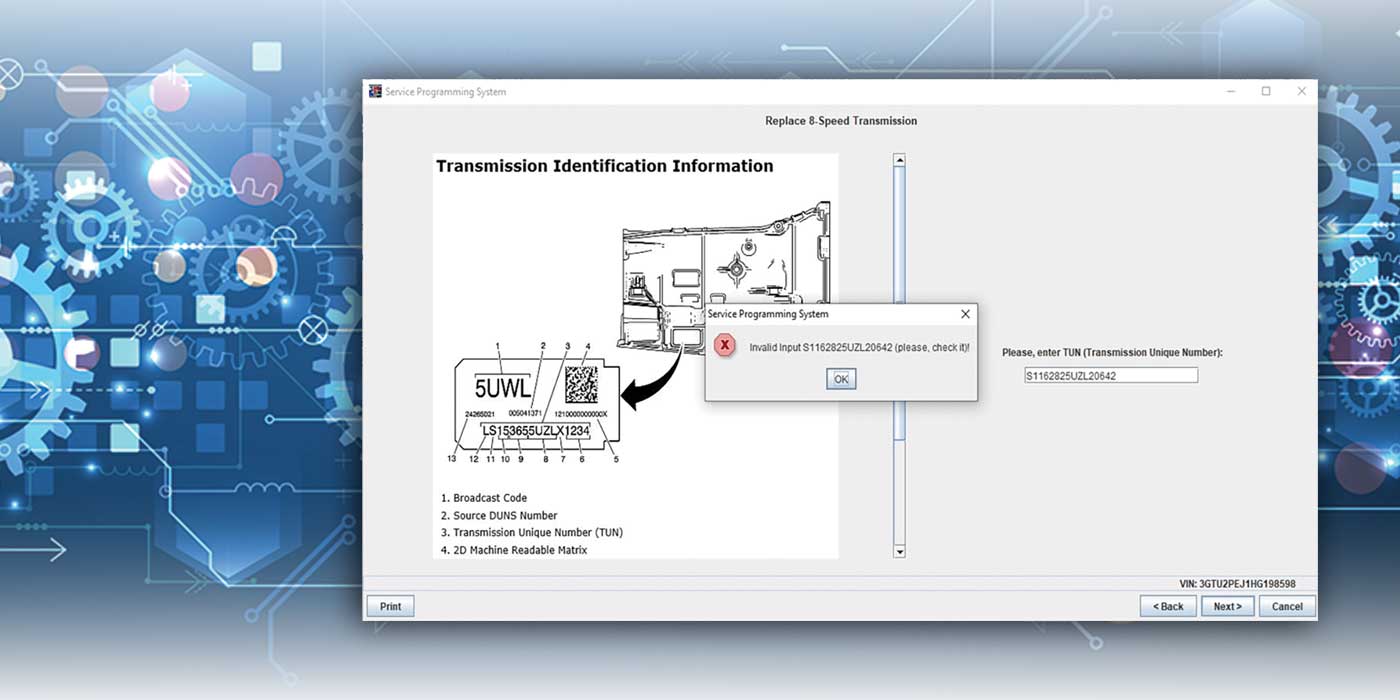

The diagnosis was straightforward, and I knew what we needed to do to get this Ram back on the road. The customer was given the repair timeframe and cost to install a remanufactured transmission, clean the battery terminals, and flush the cooler with the Hot Flush machine. The customer approved the repairs, and we proceeded with the transmission replacement.

The work was completed without any other additions, so it was handed back to me for a final drive and recheck. Everything was working well on the road test until I did a forced 3-2 downshift. There was a delay, and then, bang! It slammed into second gear. I tried it a few more times with the same result. I performed a “Quick Learn” before I started the road test and observed the CVIs, but nothing seemed to be out of line, so I returned to the shop and began the QL procedure again for good measure. I went out for another drive and had a hard forced 3-2. More diagnosis was necessary.

Anyone who regularly builds these knows there are issues with the valve body and pump that may need attention. We have vacuum testing stations in our facility, and we rarely see any valve body issues with these units. So, now what? It seemed the problem had to be in the valve body, right? Well, that is the road I went down.

I ordered a replacement valve body from our warehouse and installed it. Unfortunately, I had the same problem – hard forced 3-2 downshifts. I then drove the vehicle with the scan tool connected, monitored the PIDS, and made recordings. I could not see anything wrong, so it was evident that the remaining diagnosis wouldn’t be simple. It was time to get serious and break out the lab scope, and hope to see something irregular to send me down the right path.

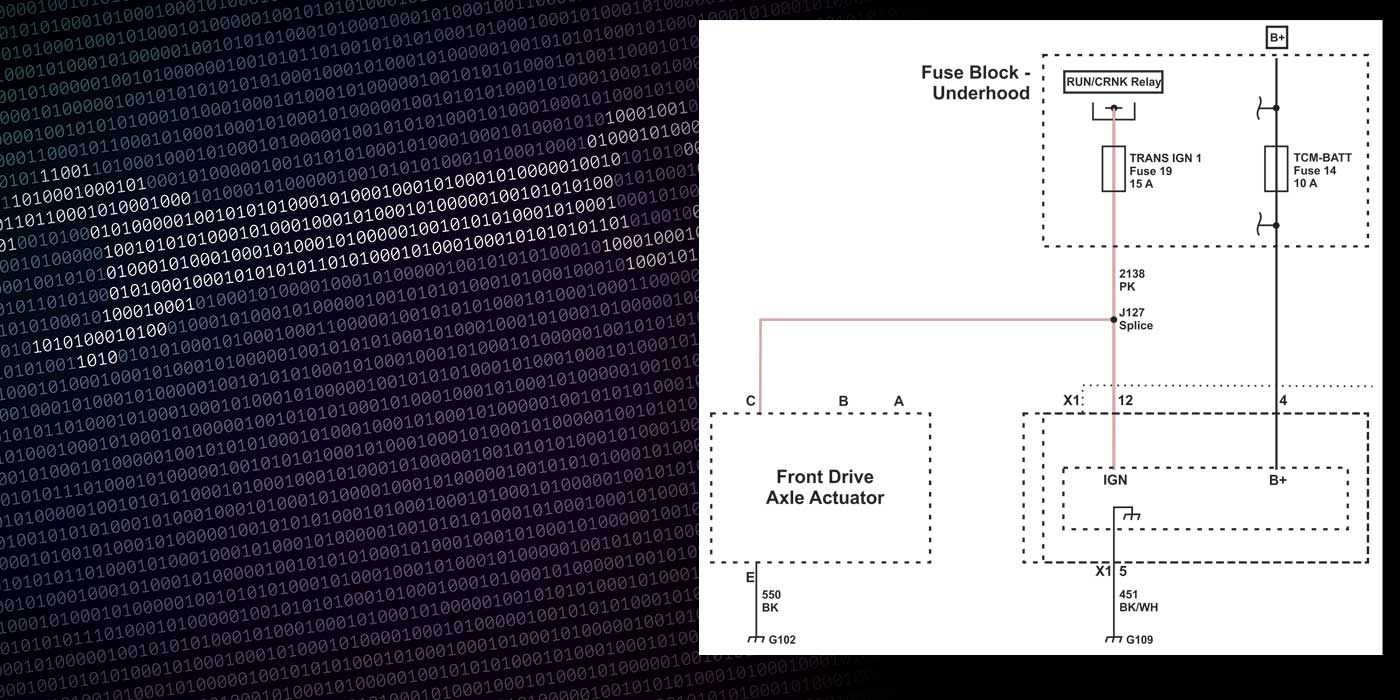

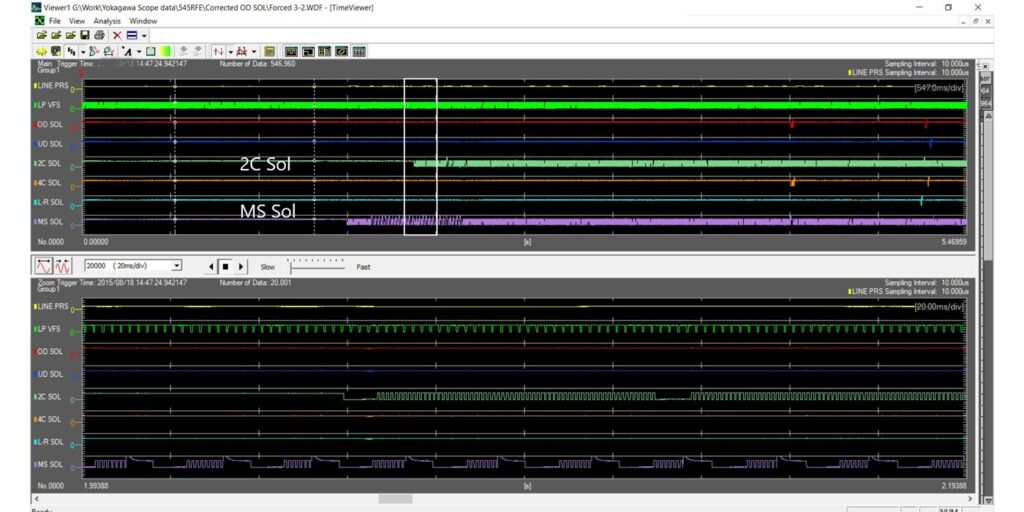

Since there were five solenoids that I wanted to look at initially, I needed to use our scope capable of displaying ten channels. My initial setup was to look at the low/reverse, underdrive, multi-select, 2C and 4C solenoids. I did not connect to the line pressure solenoid as the pressures looked good from the initial scan data. The problem always seemed to worsen when the truck was hot, so I let it run for a while before we went off to record data. Our scope can record data, so rather than looking at it live, I triggered a recording as the problem reared its ugly head.

The illustration is a screenshot of what I saw while reviewing the data. The top section is a complete recording, and the bottom is a zoomed-in view (See Figure 1, above).

Neither the multi-select nor the 2C solenoid patterns looked correct. I had my suspicions, but I didn’t want to make the same mistake again. After checking every wire going to the transmission from the PCM for any short-to-ground or short to another wire and then load-testing all the solenoid control wires, everything checked out and was eliminated as the cause.

I was down to replacing the PCM, so I ordered a new one from our local dealer. It was going to be four or five days before the new one showed up, so in the meantime, I reconnected the scope up to look at a few more items. I was not in a time crunch at this point, and more data is always better, right? I added the Pico pressure transducer, line-pressure, and overdrive solenoids so I could observe.

Remember when the customer said that the transmission had been having shifting issues for some time before the failure happened? When we called him and explained what was going on and why it needed a PCM, the customer explained that the “shifting issues” were a bang when slowing then accelerating. I might’ve saved s step from the beginning had I known this information, but I was the one who jumped to replacing the VB, and I own that.

I installed the new PCM, programmed it with the latest calibration, and set up the scope for another road test. The transmission performed flawlessly with no delay, no bang on the 3-2, and all shifts were good.

Figure 2 is a screen capture showing the recording after the PCM was replaced.

The sample rate was the same at 10us (10 microseconds), so I had to change the “ms per division” due to adding channels and recording time. Because of this, the patterns looked a bit different, but I think it is clear that the PCM replacement worked by comparing the two patterns.

While some extended diagnosis was required to resolve the issues completely, the takeaway is that repairing the obvious does not always fix the root cause. Drilling down through the process of elimination resulted in a complete repair and a happy customer.