Up to Standards

- Subject: Causes of manual-transmission failures

- Essential Reading: Rebuilder

- Author: Mike Weinberg, Rockland Standard Gear, Contributing Editor

The most-abused components in a vehicle are the clutch and the manual transmission, as these components are completely at the mercy of the driver. Most of this discussion will be tilted to performance vehicles, because they make up the vast majority of domestic cars that are still available with “stick transmissions.” The same parameters of this discussion also apply to foreign cars and, of course, the few pickup trucks and SUVs that are still optioned with a manual transmission.

The driver who chooses a manual transmission does so for more-complete control of the driving experience. On the domestic side the only real volume of manually shifted vehicles you will see in your shop are Corvettes, Vipers, Challengers, Camaros, GTOs, Cadillac CTS-Vs and Mustangs, some of which will be used in actual competition by weekend warriors and others will be tried out for enjoyment and to impress the female of the species.

The road to ruin begins with the clutch. The primary issue with transmission damage is an improperly releasing clutch. A worn or slipping clutch causes a lack of torque transfer from the engine to the transmission but does the transmission little or no harm. To have the synchronizers in the transmission function properly for smooth, clash-free shifts, the clutch must release fully when the driver depresses the clutch pedal, disconnecting the engine from the transmission completely and cleanly.

The amount of pedal travel (2-4 inches on average) will result in an air gap at the disc of about 0.050 inch. The engine is not transferring torque into the transmission, and the output shaft of the transmission is now being driven by the drive wheels. If there is no disconnect between the engine and transmission because of an improperly adjusted clutch travel, the synchronizers are now fighting the engine torque load. This causes grinding, notchy shifts that will destroy the synchronizer or blocker rings, the engagement teeth on the speed gears and synchro sliding sleeves, the synchronizer keys, shift-fork pads and the forks themselves.

Whenever you see the steel keys broken or sheared off, there can be only a few causes. The first is improper or no clutch release, driver error whereby the clutch is not released, or a driver who is trying to shift without using the clutch or is moving the shift lever before the clutch has released, rushing the shift.

A common attempt at curing this problem is frequently to use billet solid keys, because the common error is to put the fault on the factory keys. If the clutch-release issue is not resolved, the billet keys may be tough enough to survive their environment, but the synchro rings will crack or the key slots will distort, the synchro hub may crack, or a shift fork will break. None of this is the fault of the key but a result of either the driver’s bad habits or the synchronizer trying to overcome all the torque load transmitted at the crankshaft. Tremec, ZF and many other manufacturers have stopped using keys in the synchronizers, replacing them with spring-loaded balls and struts. These components will handle more abuse without breaking, but in the end the synchronizers and speed gears will die of torque-induced fatigue.

Another point of early transmission failure is an incorrect choice of clutch for the application. This usually begins with the idea that installing a performance clutch will improve the vehicle’s performance. There are a great variety of clutch sets available on the performance side, and many car owners do not understand what they were designed for when making a purchase. The correct setup will definitely improve performance over stock, and an incorrect clutch will make driving a misery and create big-time transmission failure.

We see all the time that an owner has opted to install a full racing clutch in a street-driven vehicle. In many instances the friction material is way too aggressive for use in traffic and shock-loads the gear train, causing broken inputs, clusters and speed gears, as well as possible damage to the differential and driveshaft.

It is very important to match the clutch to the vehicle usage. A car that is driven only on the track can handle more-aggressive setups, but a car that is a daily driver with occasional trips to the drag strip will be no fun to drive in traffic with a clutch that acts like an on/off switch. This happens frequently in light trucks when somebody’s cousin tells him that the way to go is a ceramic button type of disc instead of the factory woven friction material. They both will work, but the aggressive grab of the button clutch puts the transmission at risk as well as making his girlfriend puke sick. Again, if the clutch is not releasing properly, the button-type or dual-disc clutches will increase the failures dramatically.

One other issue that results in very rapid transmission damage similar to overly aggressive clutch friction material is the choice of the clutch disc itself. The vehicle was manufactured with a clutch disc that had a sprung hub. This allows the disc as it engages the flywheel and pressure plate to turn against the springs in the hub, absorbing the shock load and removing harmonic vibrations that cause gear rattle and other noise issues due to engine harmonic vibrations.

In the quest for better performance the owner may substitute a solid or unsprung clutch disc, eliminating the cushioning effects engineered into the OEM product. An unsprung clutch hub should be used only in a purpose-built race vehicle in which the owner intends to freshen up the clutch and transmission every race or two. The unsprung hub will definitely shorten the component life of the transmission.

Another cause of transmission failure is lubrication. Everyone knows that lack of lube fill due to leaks or lack of maintenance is the kiss of death for any component, but the type and quality of lube are very misunderstood. Modern synchronizer rings are designed to be used with a specific lubricant, which will be specified in the owner’s manual. A synchro ring is a wet clutch, designed to grab the cone of the speed gear during a shift and speed it up or slow it down to match the input-shaft speed to that of the output shaft.

These rings are manufactured from many different compounds, each of which has a different coefficient of friction. Brass and bronze rings have been replaced in many units by sintered-metal or carbon-fiber rings. There are no modern units left that will run on the old 75/90-weight gear oil. That oil is too thick to be exhausted from under the ring in the milliseconds it takes to make the shift, and since many of the new compounds are porous, if an incorrect oil is used the ring will continue to be impregnated with it and will never function properly. Always be sure to use an oil that is specified for the model of transmission in the vehicle. There are improved aftermarket oils, but be careful, as many contain compounds that carbon-fiber rings in particular will not do well with.

The amount of lubricant is also critical for shift timing. Overfilling a manual transmission will cause fluid to leave from the vent but will create windage problems. Windage is the effort needed for the gears to turn through the oil level. Dry-sump race engines make more horsepower than a stock wet-sump motor because the crankshaft is not fighting the oil in the bottom of the pan. Think of it as trying to run on a beach. It takes little effort to run on the hard-packed sand near the tide line but a great effort to run through 6 inches of water in the surf.

When a manual transmission is overfilled and the driver makes a shift, the gear train slows very quickly when the clutch is depressed because of the fluid drag, altering the synchronizer timing and causing shift issues. A classic instance of this was the Tremec 3650 series of five-speed transmissions on which the fill plug was actually placed too high in the case. On these units you cannot “fill to spill” but to 1/2 inch below the fill-plug level for proper operation.

An area that creates more transmission issues is the shifter. It is common to install a “short-throw shifter” into a vehicle equipped with a manual transmission. The shifter is designed to shorten the amount of movement in the stock shifter, making the shifts take place more quickly. There are many excellent short-throw shifters on the market, and they do improve the shift sequence. However, the driver needs to understand that the time it takes to shift is predicated on how fast the synchronizer can complete the shift without gear clash. When you shorten the throw of the shifter it is possible for the driver to be moving the stick faster than the clutch can release fully, and before the synchronizer can complete the function of matching the speeds of the input and output shafts. This results in grinding or blocked-out shifts, as the timing has been altered for the function of the components.

Another issue we have seen over the years is the lack of vibration-deadening construction on some aftermarket shifters. The auto manufacturers spend a fortune trying to isolate the interior of the car from all outside noise, vibration and harshness (NVH). Some aftermarket shifters will create a “buzz” from the stick, or other noises not heard or felt with the factory stick. In any event a short-throw shifter will complicate transmission failure due to a poor clutch release or out-of-time synchronization.

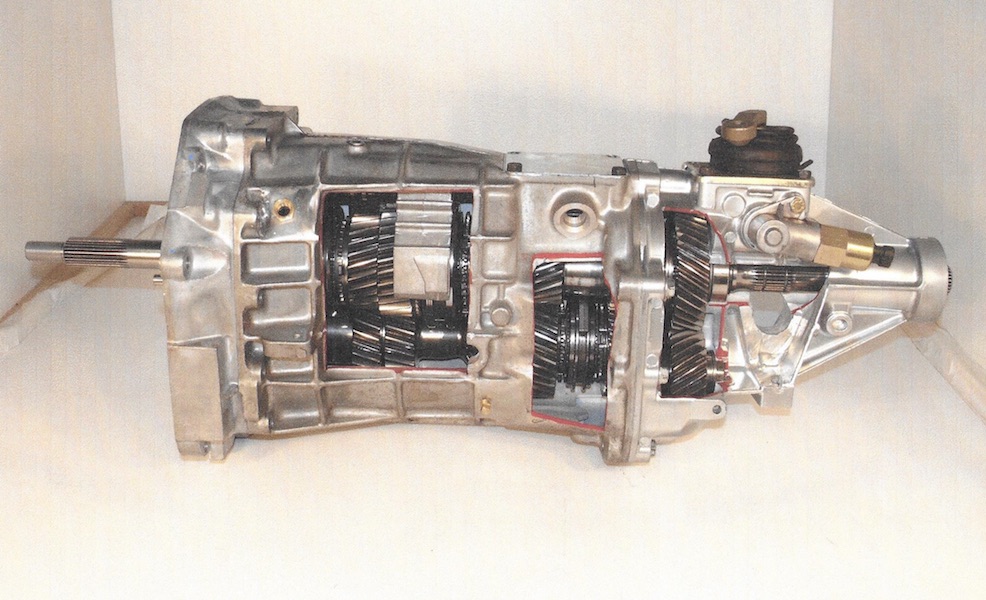

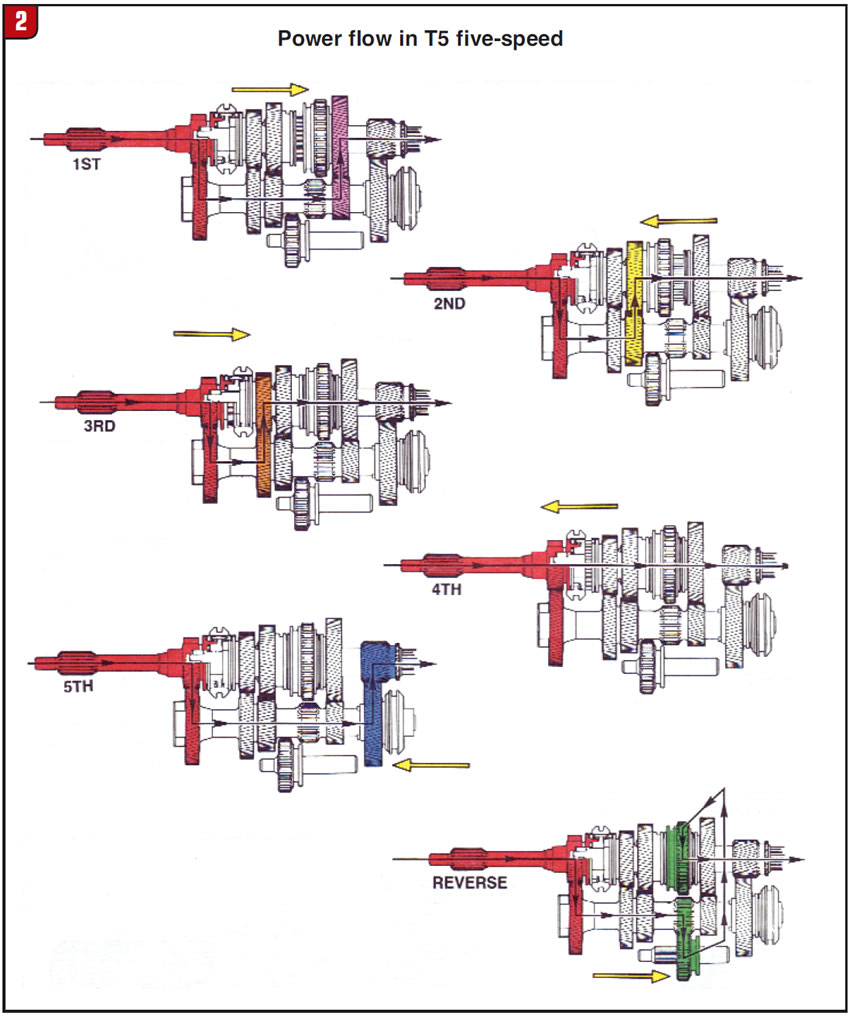

The art of synchronization is poorly understood by most drivers. The synchronizer is like a zipper. Everyone knows how to use it, but few understand how it really works. The basic understanding begins with the design of the manual transmission. We have an input shaft that is splined to the clutch disc and transfers torque (rotational force) from the engine crankshaft into the gearbox. The input shaft is in line with and rides on the nose of the mainshaft (output shaft) of the transmission but can turn independently from the mainshaft. The gear end of the input shaft meshes with a countershaft or cluster gear that is mounted parallel to the input and output shafts in the transmission case. This drives the cluster gear, which has multiple gears on it that mesh with the speed gears mounted on the mainshaft. The speed gears are freewheeling on the mainshaft.

Then we have the synchronizer assemblies that are splined to the mainshaft between the speed gears. All the speed gears, which include the input gear, have a second set of teeth on them that engage the sliding sleeve on the synchronizer assembly. When a shift is made the shift fork slides onto the engagement teeth of the speed gear, and that gear is now attached to the mainshaft and transmits power from the input through the cluster gear and back into the mainshaft, driving the wheels of the vehicle.

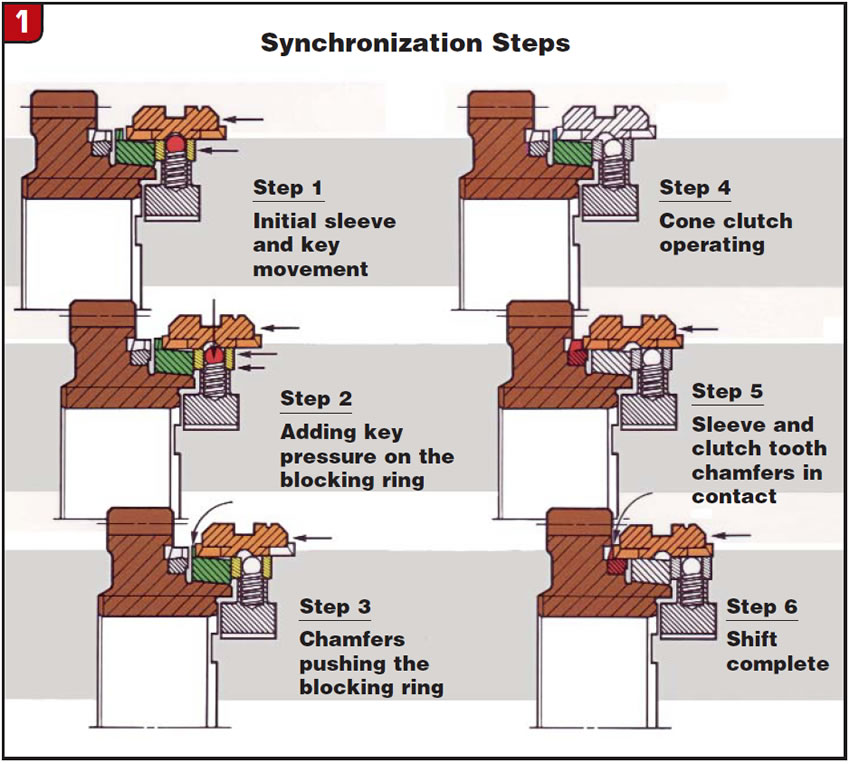

On a six-speed transmission you will have a 1-2 synchronizer, a 3-4 synchronizer and a 5-6-reverse synchronizer. If the synchronizer sleeves are all centered the transmission is in neutral. The synchronizer must have a way to engage the spinning gear without grinding. Between the synchronizer hub and the speed gear is the synchronizer ring (blocking ring) and a single or multiple set of cones that are attached to the speed gear. The synchro ring or rings turn with the synchronizer and are located in position by keys or struts that sit in the synchronizer body and move with the sliding sleeve.

As the driver moves the shift lever to select a gear, the synchro keys force the synchro ring or rings onto the machined cone of the speed gear, slowing it down or speeding it up to match the speed of the output shaft, which is being rotated by the driveshaft. With the clutch pedal depressed, the input gear is now rotating at engine speed, which is considerably slower than that of the output shaft if you have a proper clutch release. The synchro ring can rotate slightly within the sliding sleeve and the teeth do not line up with the engagement teeth on the speed gear. When the shaft speeds equalize, the ring will move in a circular motion enough for the sliding sleeve to completely engage the speed gear and complete the shift (Figure 1). This is why they are also called blocking rings, as they block the sleeve from full engagement until the speed gear and shaft are at the same speed so that the shift is completed without grinding.

None of this will work unless the clutch can fully release and disconnect the torque from the crankshaft to the input. If you do not have that disconnect of the power flow, you are now trying to stop or slow 400-plus lb.-ft. of torque in the motor with a small friction surface that may be 3 or 4 inches in diameter and 1/4 to 1/2 inch wide. This immediately damages the friction material of the ring and can shear off the synchronizer keys like a guillotine. Once that happens you will have blocked-out or grinding shifts as the sliding sleeve clashes with the engagement teeth on the speed gear.

Upshifts require a lot less synchronizer effort than downshifts. Drivers who wish to slow the vehicle by using the transmission find out that brakes are a lot cheaper than transmissions. Careful shifting, particularly on downshifts, prevents a shift from 5th to 1st, which is really hard on the transmission and engine. Rev limiters in modern cars prevent over-revving the motor on upshifts but cannot control engine speed on downshifts.

We get many calls from people who have rebuilt their transmissions and now have bearing-noise issues or notchy shifts. If you are rebuilding the gearbox it is very important to thoroughly clean all the components, including the synchronizer assemblies. Before taking the sliding sleeve off the synchronizer hub, match-mark the hub and the slider so that it can be reassembled on the same splines. Metallic debris will accumulate between the slider and the hub, and if you do not clean them completely fresh lube will wash out the metal, causing premature bearing failure.

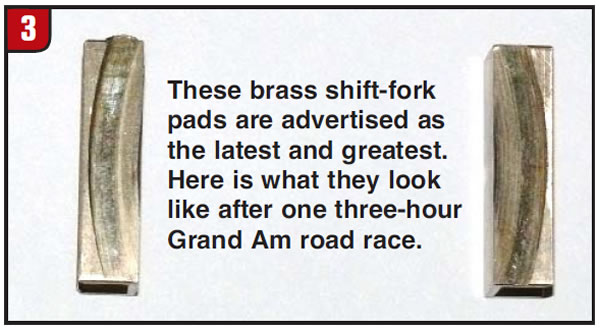

When there is a synchronizer failure, the shift-fork pads will suffer. Many people opt to replace the plastic pads with brass or bronze pads (Figure 3) as an upgrade. There is no reason to do this. The sliding sleeve is machined at the fork groove with a micro finish that is designed for plastic pads, not metal. If the clutch is fully released there is very little load on the fork pads. Using metal pads as an upgrade is a waste of money, creates noises that were not there before and will lead to premature pad wear.

The fork and the detent system that keep it in place cannot hold the slider in position on the gear. The engagement teeth on the speed gear and slider have a back taper engineered into them to prevent the slider from hopping out of the gear under changing throttle positions. If the pointing of the engagement teeth has been rounded off because of a bad synchronizer ring the gear will be hard to shift into and should be replaced. If the back taper is worn out of the engagement teeth on the speed gear and slider you will get gear jump-out.

As you can see, most transmission failures begin outside the transmission with a poor clutch release or a sloppy driver. In vehicles equipped with automatic transmissions, the driver has very little control over the shifts, but the manual transmission has to rely on the driver to shift properly and fully release the clutch every time.