Technically Speaking

- Subject: Rebuilding continuously variable transmissions

- Units: 01J, CFT30, JF011E, VT20/25-E

- Vehicle Application: Audi A4 & A6, Honda, GM, Ford, Dodge, Jeep, Mitsubishi, Nissan

- Essential Reading: Rebuilder, Shop Owner, Diagnostician

- Author: Wayne Colonna, ATSG, Transmission Digest Technical Editor

The question of whether to rebuild a continuously variable transmission (CVT) has increased dramatically this past year on our technical hotline, and I thought I might risk making a few comments about this subject.

The call comes to our technical hotline a few different ways. The question has been: “Why are people saying you cannot rebuild CVTs?” or, “Is it worth trying to rebuild one of these” or, “What am I getting myself into if I try to rebuild one? What tools do I need?”

My answers to these questions follow.

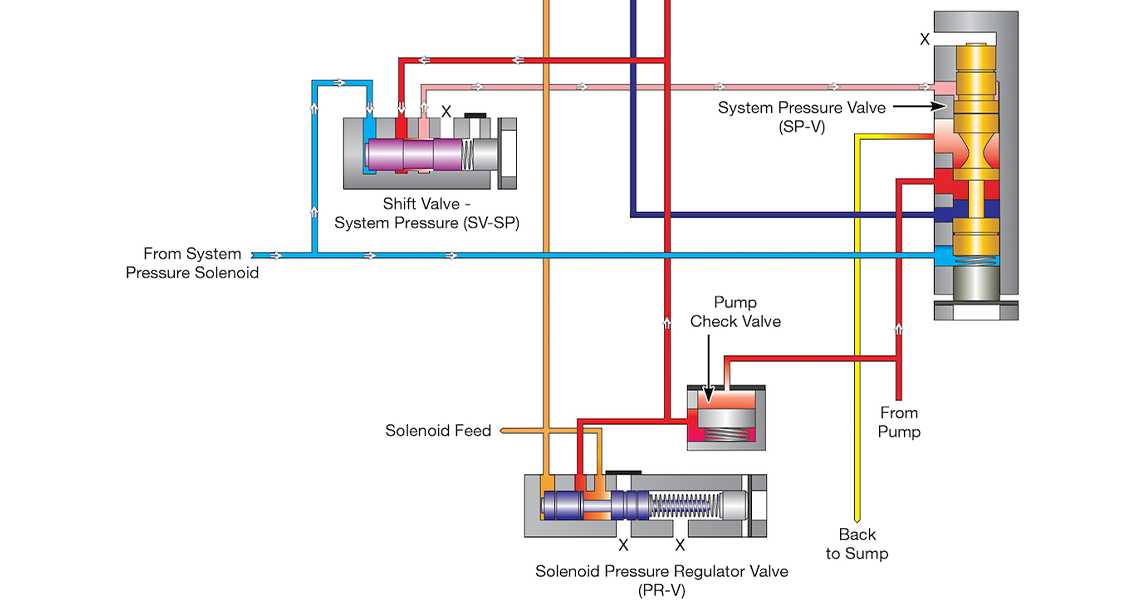

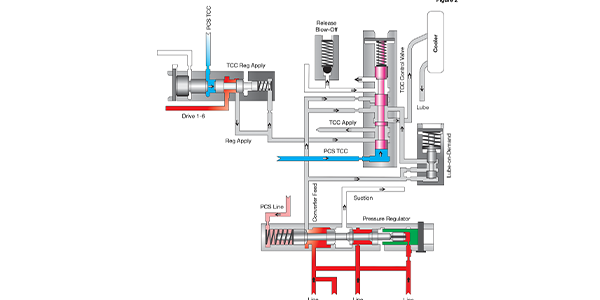

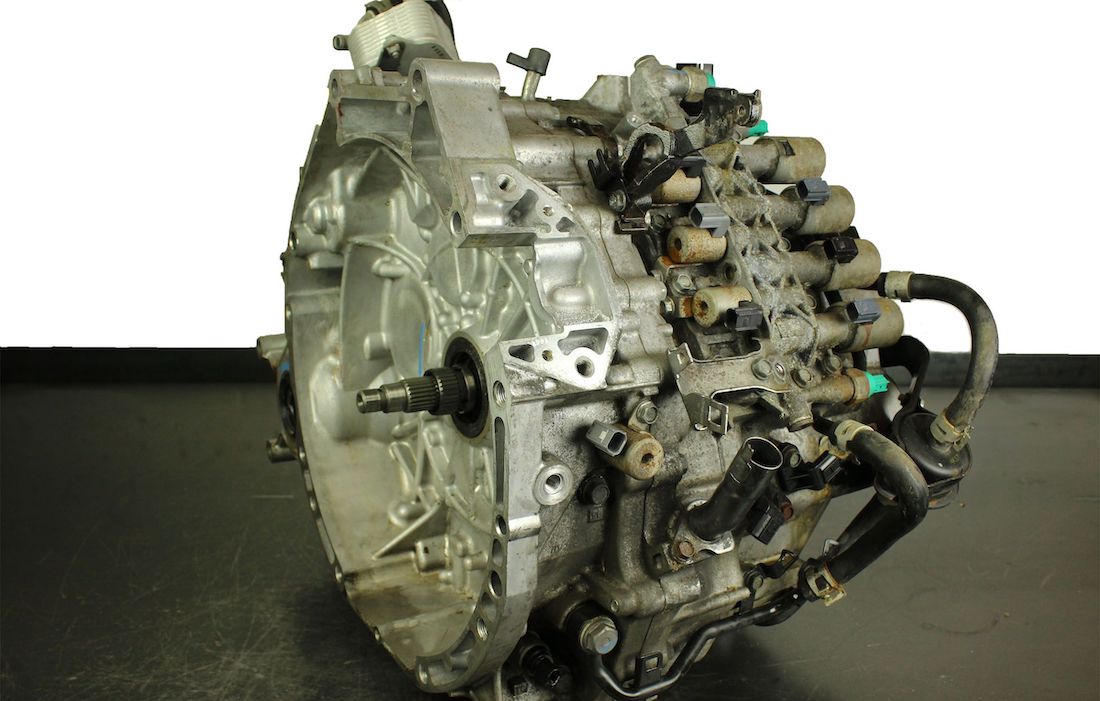

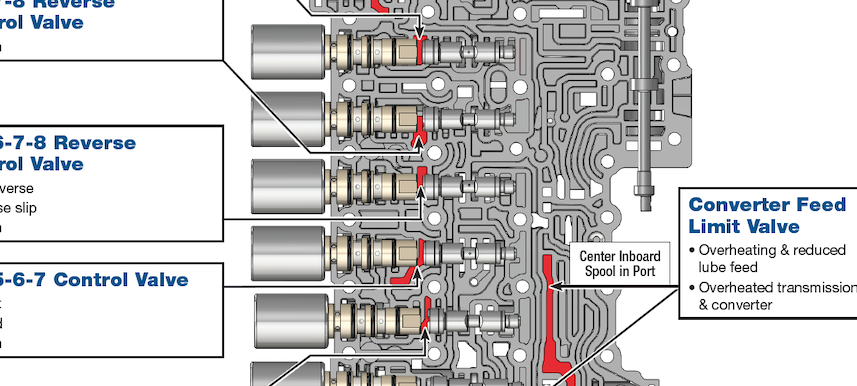

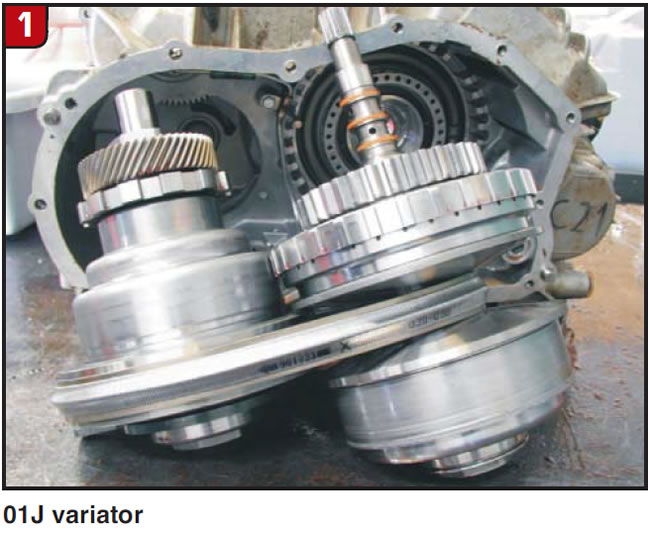

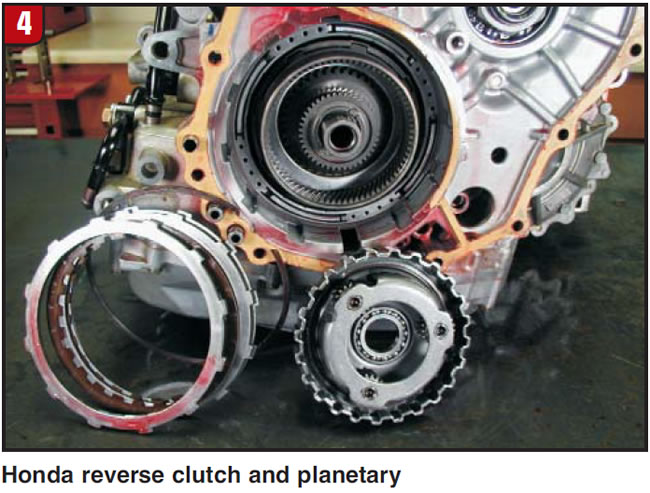

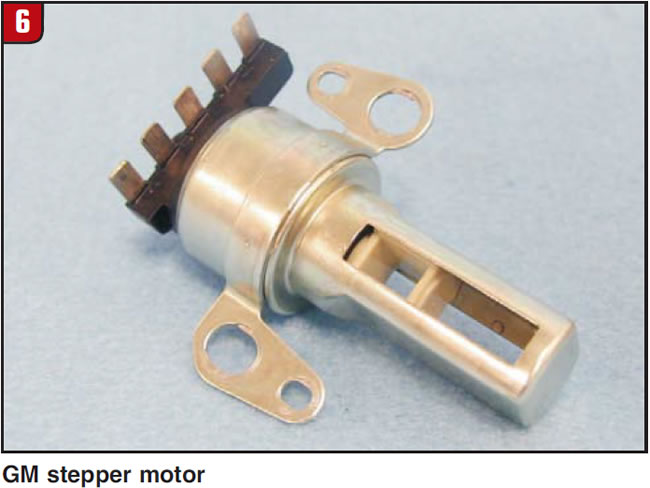

CVTs are not complicated transmissions; in fact, they are quite simple. Generically they all basically have a drive- and driven-pulley assembly (otherwise known as a variator), a forward clutch, a reverse clutch, a planetary gear set, a valve body, solenoids and perhaps a stepper motor (figures 1 through 6).

Basic differences between them can be the way engine torque is supplied to the transmission. Some use a torque converter; others may use a dual-mass-style flywheel. In these instances a clutch inside the transmission has to release at a stop and re-apply when the driver accelerates. By understanding this you have a good general idea of all CVTs. From there you can learn the individual personalities of each CVT. One such example is the JF011E, which has a ROM device on the valve body. This is where all the vehicle specifications are stored, so that ROM must stay with the vehicle if you are swapping valve bodies.

All in all, CVTs are not complicated transmissions. They are basically very simple. So what’s the deal with rebuilding them? At the moment, the biggest show stopper basically comes down to two obstacles:

- Parts availability

- Their prices if the parts are available.

To be able to make the right judgment call in determining the type of work that will be most profitable, first look into the worst-case scenario: How much will it cost to replace the entire transmission (preferably with a remanufactured or new CVT as opposed to a used one, since you have no idea whether a used unit is any good)? Then look into availability of parts and their prices should rebuilding or repairing it be considered. Take, for example, Ford’s CVT. These units are known to have problems with failure of a bearing that at one time was available separately. Ford no longer sells this bearing, making the unit difficult to repair.

At some point throughout this process it would be helpful to determine the type of problem and/or damage the CVT has. If there are electrical codes related to a failed TCM, solenoids or internal wiring, this may require the purchase of an entire valve-body assembly to acquire the TCM, solenoids and harness – something we are already all too familiar with in non-CVT units (most CVTs do NOT have the TCM in the transmission on the valve body).

If it is just forward- or reverse-clutch damage and the variator (pulleys-and-belt unit) is good, there is a straightforward repair.

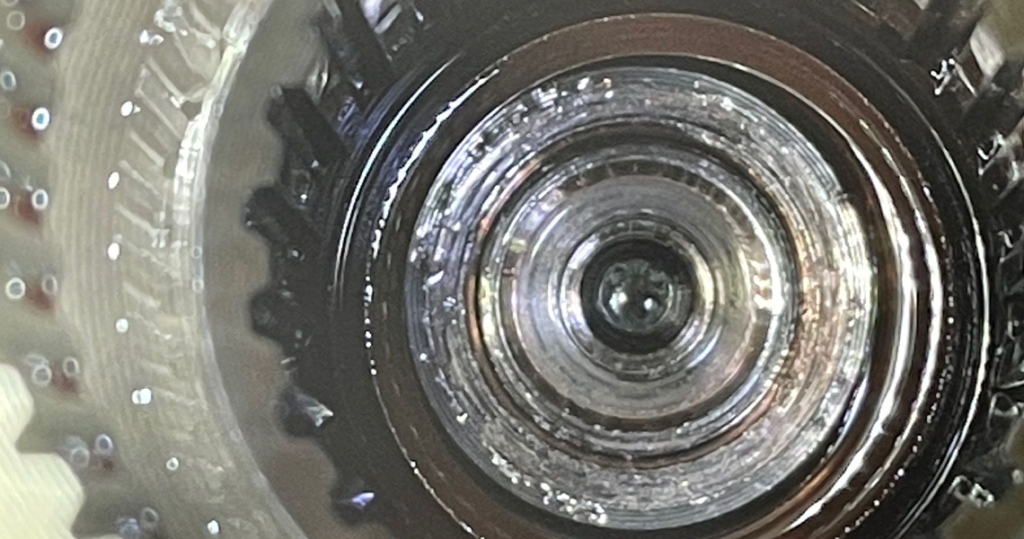

If the variator assembly is destroyed, a major repair is involved. I have heard of places that are machining the surfaces of damaged pulley faces, but I have a couple of questions regarding that process:

- Where are they getting the O-rings, square-cut rings and related seals to replace the old? Also, many (not all) of the driven pulleys are not designed to be disassembled.

- Where are they getting new belts, and how much are they?

My point is that at the moment the normal shop does not have access to either these items or the special tools, if there are any, to disassemble many of these driven-pulley assemblies.

Most technicians check to see whether the pulley assembly is good by just looking at the face where the belt rides for scoring due to the belt slipping. Another way is to be able to pressurize each pulley to see whether it holds pressure. These pulleys always clamp down on the belt. The pressure to open and close the pulley may vary, but there is always pressure clamping down on the belt. If adapters are made to allow high pressure to clamp down on the belt, leaks can be detected. If there are no leaks, and the pulley face is smooth, you have a good variator assembly.

As mentioned earlier about learning the individual personalities of each CVT, there will be learning curves involved for those who have yet to dip their toes in the water. The most-common units being worked on today in the U.S. are the 01J CVT in Audi A4 and A6 vehicles and Honda CVTs. GM’s VT20/25-E and Ford’s CFT30 are two others running right behind them. Up and coming is the JF011E-type CVT used in Nissan, Mitsubishi, Dodge and Jeep vehicles. Each one has its own idiosyncrasies but has made shops money after they have learned their individual traits as well as knowing how to price the work.

In conclusion, as parts and special tools (where needed) become available and affordable, rebuilding CVTs will become a more-enjoyable and profitable experience. Until that time, caution is required as to how to proceed, as you are not in business to lose money.